Kingdavidkalakaua dust

King David Kalākaua: The Merrie Monarch Who Sought to Revive Hawaiian Culture

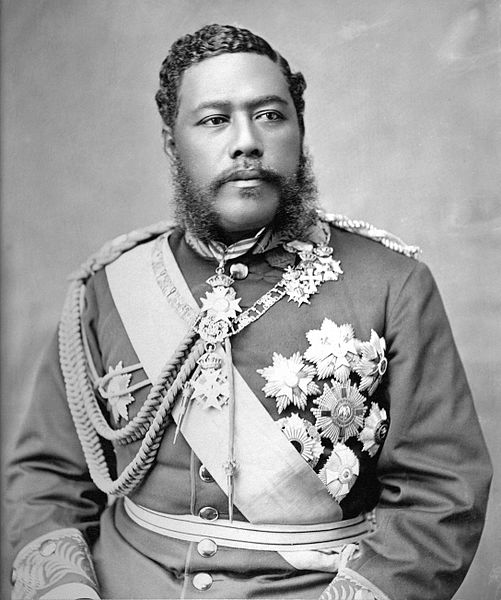

King David Kalākaua - The Merrie Monarch who revived Hawaiian culture, promoted international diplomacy, and built the iconic 'Iolani Palace.

King David Kalākaua (1836–1891), often called the "Merrie Monarch," was the last reigning king of the Hawaiian Kingdom. He was a visionary leader, cultural revivalist, and an ardent defender of Hawaiian sovereignty during a time of increasing Western influence and political pressure. Known for his charismatic personality and love for Hawaiian traditions, Kalākaua made significant efforts to restore the cultural identity of Hawaii while navigating the complex political landscape of the 19th century. His legacy is marked by the revival of hula, the celebration of Hawaiian arts, and the construction of the iconic ʻIolani Palace, as well as the unfortunate events that led to the decline of the Hawaiian monarchy.

Early Life and Ascension to the Throne

David Laʻamea Kamanakapu'u Mahinulani Naloiaehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua was born on November 16, 1836, in Honolulu, Oahu. He was part of the Hawaiian nobility (ali'i class) and was closely related to the ruling Kamehameha dynasty through his mother, Analea Keohokālole. His father, Kapa'akea, was also a high-ranking chief. Kalākaua's upbringing combined both traditional Hawaiian customs and Western education, giving him a unique perspective that would later shape his reign.

Kalākaua was educated at the Royal School, which was established by American missionaries to educate the children of Hawaiian royalty. There, he received an education that included English, mathematics, and other subjects typical of Western schooling, alongside instruction in Hawaiian traditions and history. His early education made him well-versed in both Hawaiian and Western thought, a combination that would later influence his policies as king.

The political situation in Hawaii during Kalākaua's youth was marked by increasing foreign influence and internal power struggles. After the death of King Kamehameha V in 1872 without an heir, a constitutional crisis ensued. Kalākaua was initially a candidate for the throne but lost to Lunalilo, who was chosen by the Hawaiian legislature. Lunalilo's reign was short-lived, however, and upon his death in 1874, Kalākaua ran for the throne once more, this time winning the election against Queen Emma, the widow of Kamehameha IV.

The Early Reign of King Kalākaua

When Kalākaua ascended to the throne, Hawaii was undergoing a period of profound change. The kingdom faced external pressures from foreign powers, particularly the United States, which was interested in Hawaii for its strategic location in the Pacific and its valuable sugar industry. Internally, there was growing discontent among both native Hawaiians and foreign settlers regarding land ownership, political power, and economic control.

One of Kalākaua's early acts as king was to embark on a mission to restore the prestige and cultural traditions of the Hawaiian monarchy, which he felt had been eroded by Western influences. He believed that by reviving Hawaiian arts, music, and customs, he could strengthen the cultural identity of his people and reinforce their sense of pride and unity. This mission led to his nickname, the "Merrie Monarch," reflecting his love for music, dance, and celebration.

The Revival of Hawaiian Culture

Kalākaua's commitment to cultural revival was most evident in his efforts to bring back traditional Hawaiian practices that had been suppressed under the influence of Christian missionaries. One of his most significant achievements was the revival of hula, the traditional Hawaiian dance form that had been discouraged by missionaries who viewed it as pagan and immoral. Kalākaua saw hula as a vital expression of Hawaiian identity and spirituality, and he actively promoted its performance at royal events and celebrations.

In 1883, Kalākaua organized the Royal Hawaiian Coronation, a grand ceremony that included hula performances, chants (mele), and other traditional arts. This event was a public declaration of his dedication to reviving Hawaiian traditions. He also established the Hale Naua Society, a royal society dedicated to preserving and promoting Hawaiian culture, arts, and sciences. Through this society, Kalākaua encouraged the study and practice of ancient Hawaiian crafts, storytelling, and knowledge systems.

Kalākaua was also a prolific composer and musician, writing several songs and chants that are still popular in Hawaii today. His most famous composition, "Hawaii Pono'ī", became the national anthem of the Hawaiian Kingdom and remains the state song of Hawaii. The lyrics of the song celebrate the strength and resilience of the Hawaiian people, encapsulating Kalākaua's vision of a proud and united nation.

The Construction of ʻIolani Palace

One of Kalākaua's most enduring legacies is the construction of ʻIolani Palace, the royal residence of the Hawaiian monarchs. Completed in 1882, ʻIolani Palace is the only royal palace on American soil and stands as a symbol of the sophistication and grandeur of the Hawaiian monarchy. Kalākaua envisioned the palace as a statement of Hawaii's sovereignty and its place among the world's nations. The palace was equipped with the latest technologies of the time, including electricity, indoor plumbing, and a telephone system, showcasing the kingdom's modernity.

ʻIolani Palace was not only a royal residence but also a center of political activity. It hosted numerous state dinners, diplomatic receptions, and cultural events, serving as a venue where Kalākaua could promote Hawaiian culture and engage with foreign dignitaries. The palace became a symbol of Kalākaua's efforts to modernize the kingdom while preserving its unique cultural heritage.

The Political Challenges and the Bayonet Constitution

Despite his efforts to revive Hawaiian culture and strengthen the kingdom, Kalākaua faced significant political challenges during his reign. By the 1880s, foreign interests, particularly American business interests tied to the sugar industry, had become increasingly powerful in Hawaii. The United States exerted considerable pressure on the Hawaiian monarchy to secure favorable economic agreements, including a reciprocity treaty that allowed Hawaiian sugar to enter the U.S. market duty-free.

Tensions between the Hawaiian monarchy and foreign settlers culminated in the Bayonet Constitution of 1887, a pivotal moment that dramatically altered the course of Hawaiian history. Kalākaua was forced, under threat of violence, to sign a new constitution that severely limited his powers and disenfranchised many Native Hawaiians. The Bayonet Constitution was effectively a coup by the Hawaiian League, a group of powerful businessmen and planters, who sought to reduce the influence of the king and increase their own control over the government.

Kalākaua's authority was diminished, and the kingdom's political landscape was dominated by American interests, paving the way for the eventual annexation of Hawaii by the United States.

Kalākaua$'s World Tour: A Diplomatic Mission

In 1881, King Kalākaua embarked on an ambitious world tour, making him the first reigning monarch to travel around the globe. His journey took him to the United States, Japan, China, India, Europe, and the Middle East. The purpose of the tour was twofold: to seek new economic opportunities for Hawaii and to establish diplomatic relations with other nations. Kalākaua was particularly interested in exploring immigration agreements with Asian countries, hoping to bring laborers to work in Hawaii's growing sugar industry.

The world tour was also a way for Kalākaua to showcase Hawaii's sovereignty on the international stage. He met with numerous world leaders, including President Chester A. Arthur of the United States, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, and the Emperor of Japan. His travels demonstrated his commitment to positioning Hawaii as a respected and independent nation.

The Legacy of King Kalākaua

King David Kalākaua's reign was marked by both triumphs and tragedies. He was a visionary leader who sought to revive Hawaiian culture and assert the kingdom's independence during a time of increasing foreign dominance. His efforts to restore traditional practices, celebrate Hawaiian arts, and promote education left a lasting cultural legacy that continues to be celebrated today.

However, Kalākaua's reign also saw the erosion of Hawaiian sovereignty, culminating in the signing of the Bayonet Constitution and the eventual overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. His sister and successor, Queen Lili'uokalani, would face the final blow to the kingdom's independence, leading to the annexation of Hawaii by the United States in 1898.

His final words, "Tell my people I tried," reflect his enduring commitment to his kingdom and his people. Today, he is remembered as the "Merrie Monarch," a title that honors his love for Hawaiian culture and his efforts to keep the spirit of aloha alive. The annual Merrie Monarch Festival, a world-renowned hula competition, is held in his honor, celebrating the cultural revival he inspired.

Kalākaua's vision of a proud and culturally vibrant Hawaii continues to resonate, reminding the Hawaiian people of their rich heritage and the enduring legacy of their last king.